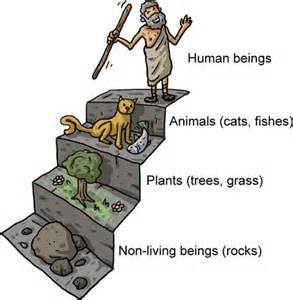

All the same, many plants had useful properties serving for food or medicine. The highest plants had attractive attributes like leaves and flowers, while the lowest plants, like mushrooms and moss, did not, and stayed low on the ground, close to the mineral earth. Plants lacked sense organs and the ability to move, but they could grow and reproduce. All, however, had the senses of touch and taste. The highest animals like the lion, the king of beasts, could move vigorously, and had powerful senses such as excellent eyesight and the ability to smell their prey, while lower animals might wriggle or crawl, and the lowest like oysters were sessile, attached to the sea-bed. Angelic beings Ĭharles Bonnet's chain of being from Traité d'insectologie, 1745 Animals Īnimals have senses, are able to move, and have physical appetites. He is the model of perfection for all lower beings. He has all the spiritual attributes found in humans and angels, and uniquely has his own attributes of omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence. God has created all other beings and is therefore outside creation, time, and space. The chain of being links God, angels, humans, animals, plants, and minerals. The minerals are, in the medieval mind, a possible exception to the immutability of the material beings in the chain, as alchemy promised to turn lower elements like lead into those higher up the chain, like silver or gold. Thus, the higher the being is in the chain, the more attributes it has, including all the attributes of the beings below it. At the bottom are the mineral materials of the earth itself they consist only of matter.

Beneath them are humans, consisting both of spirit and matter they change and die, and are thus essentially impermanent. In the end, we see that analyzing change through an analysis of contraries in change helps us to see why Aristotle divides up nature and the soul in the way he does.The chain of being hierarchy has God at the top, above angels, which like him are entirely spirit, without material bodies, and hence unchangeable. In chapter five I show that the contraries of the intellect differ from the contraries of the sensitive soul by virtue of receiving universal forms rather than the particular forms of the sensitive faculties. Chapter four argues that the changes proper to the sensitive soul differ from the vegetative soul because the sensitive faculties can receive forms without matter. In chapter three I distinguish between the changes proper to the vegetative soul by showing how those changes are not reducible to the mechanisms at work in changes between non-living bodies, and how these changes allow for the transfer of matter without form. hot, cold, wet, and dry), and I show how the mechanisms of those changes are reducible to exchanges of these primary contraries. Then I look at the fundamental contraries at work in interactions between non-living bodies (i.e.

In that chapter I argue that to understand the mechanisms of a change in Aristotle’s natural philosophy we must understand the contraries at work in that change. I begin with an investigation into Aristotle’s argument concerning the principles of change, found in Physics I.5, where we see that all natural change requires contraries as principles of change. In this dissertation I explore the reasons why Aristotle distinguishes three types of soul based on his theory of natural change. However, the reason why Aristotle divides up the soul in this way is not so clear, and the existing literature on the matter is sparse and unconvincing. Aristotle famously distinguishes between three types of soul: the vegetative soul, the sensitive soul, and the intellective soul.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)